Transactional Outbox: What is it and why you need it?

Receiving a request, saving it into a database, and finally publishing a message can be trickier than expected. A naive implementation can either lose messages or, even worse, post incorrect messages.

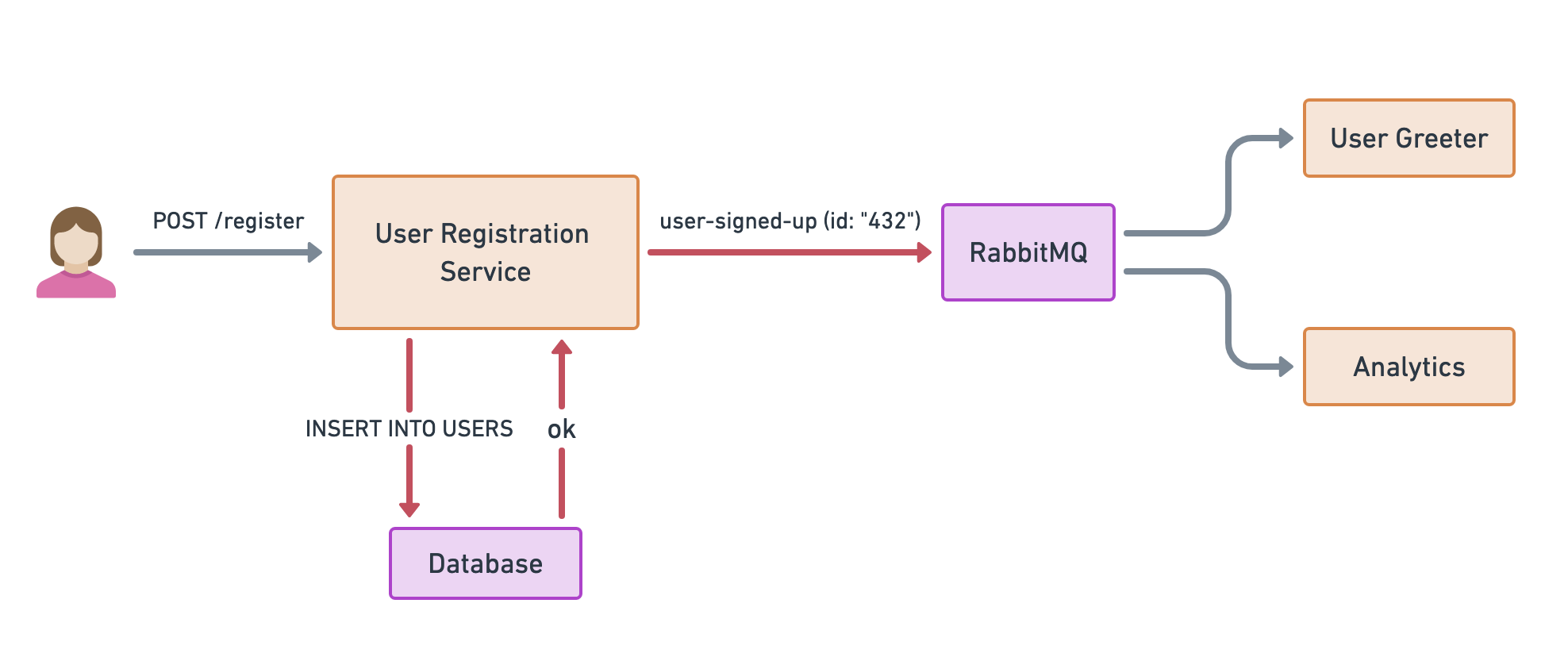

Let’s look at an example. A user registration service allows users to sign up. The backend of this system saves this request to a database and publishes a “user-signed-up” message on RabbitMQ. Based on this message, the User Greeter service sends a welcome message to the user, while the Analytics service records new signup and updates the business dashboards.

We will focus on the User Registration Service and try out several ways to implement the registration action.

Implementation 1: Publishing after the user insert transaction finishes

Our first attempt to implement the register action will be to open a transaction, save the user, close the transaction, and finally publish the message to RabbitMQ.

def register_user(name)

DB.transaction do

user = User.new(name: name)

user.save!

end

RabbitMQ.publish("user-signed-up", user.ID)

end

Let’s examine what can go wrong with this implementation. We need to answer three questions:

- What happens if RabbitMQ is temporarily unavailable?

- What happens if writing to RabbitMQ fails?

- What happens if the service is restarted right after the transaction finishes but right before the RabbitMQ message is published?

The answer to all three questions is: The user will be saved to the database, but the message will not be published to the queue. The user will not get a welcome message via email. Unacceptable!

Implementation 2: Publishing before the user insert transaction finishes

Publishing after a closed transaction leaves us in trouble. What if we try the opposite and publish the message right before we close the transaction?

def register_user(name)

DB.transaction do

user = User.new(name: name)

user.save!

RabbitMQ.publish("user-signed-up", user.ID, user.Email)

end

end

Let’s examine this approach as well. It seems that this one is also problematic.

If the transaction fails or rollbacks (for example, due to a uniqueness constraint) we will publish a message to RabbitMQ that is not correct.

The user was not created, yet we still sent a “user-signed-up” message to upstream services. Our service is lying. Unacceptable!

Problem Statement: If we publish in the transaction, we can publish a fake message. If we publish after the transaction, we are risking that we will never publish the message. How to guarantee message dispatching?

The transactional outbox pattern

Using a transactional outbox is one way to solve this problem.

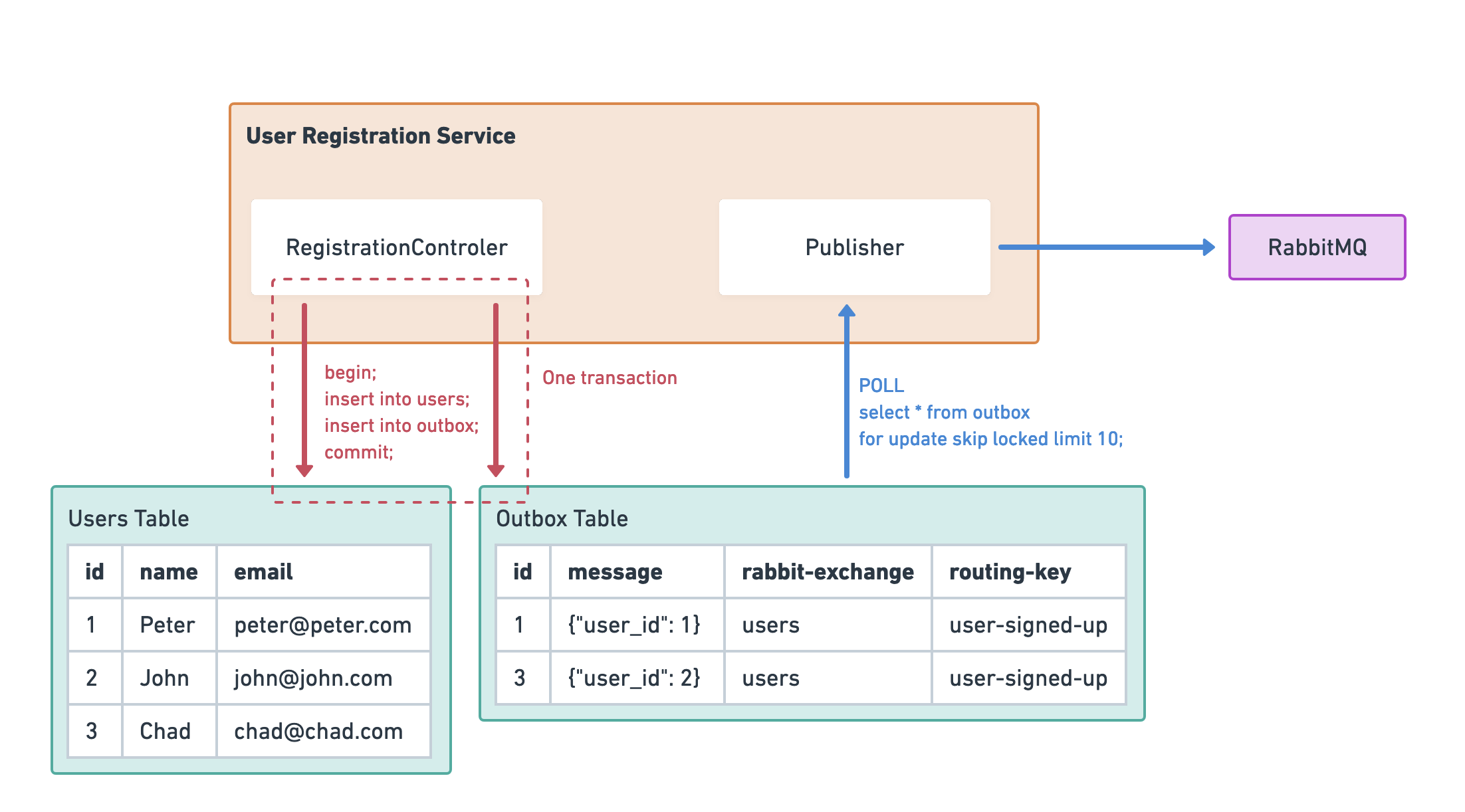

We will introduce a supplementary database table, called outbox, that will store outgoing messages from our service. A publisher service will then read from this table and publish messages to the queue.

In code, the registration controller would do the following:

def register_user(name)

DB.transaction do

user = User.new(name: name)

user.save!

outbox = Outbox.new(

"message": json({user_id: user.ID}),

"exchange": "users",

"routing-key": "user-signed-up")

outbox.save!

end

end

In the meantime, a Publisher service polls the outbox table and publishes the messages to RabbitMQ.

module Publisher

def start

loop do

poll_and_publish()

sleep(1.second)

end

end

def poll_and_publish

transaction do

# SELECT * FROM outbox FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED LIMIT 10

messages = Outbox.lock("FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED").limit(10).load()

messages.each do |msg|

RabbitMQ.publish(msg)

Outbox.delete(msg.id)

end

end

end

end

Problems resolved by a transactional outbox?

We had two problems in our original implementations:

The first attempted implementation tried to publish to the queue after a finished database transaction. This opened up the possibility of not publishing anything even if the user was persisted in the database.

We resolved this problem by moving the message creation inside of the transaction. This ensured that if a user was created, the message was persisted as well.

The second attempted implementation tried to publish inside of the transaction. Still, because we were trying to write to a different system, we published fake messages in case the user creation transaction rolled back. When I say fake message, I mean that the queue would contain a “user-signed-up” message, but the user would not be saved to the database.

We resolved this problem by writing both the user and the message into the database, which allowed us to have a clean rollback if the user creation failed.

Problems not resolved by the transactional outbox?

The transactional outbox has an at-least-once message publishing guarantee, which means that the system guarantees that the message will be published to the queue at least once if a user is created. However, it can happen that this message is published multiple times to the queue.

How this happens?

Let’s take a look at the Publisher’s implementation and find a spot where our implementation produces multiple messages:

transaction do

# SELECT * FROM outbox FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED LIMIT 10

messages = Outbox.lock("FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED").limit(10).load()

messages.each do |msg|

RabbitMQ.publish(msg)

# <--- HERE

# Our service can crash at this moment, for example. The message

# gets published but the Outbox message is not cleared up. On

# restart it will re-attempt the message publishing.

Outbox.delete(msg.id)

end

end

I’ll illustrate a possible timeline of events that causes multiple publishing in the following example:

event 01: messages = "select * from outbox"

event 02: => messages are now [{msg1, msg2}]

event 03: RabbitMQ.publish(msg1)

event 04: # message persisted to rabbitmq

event 05: *** CRASH: Out of memory ***

event 05: Publisher service is restarted.

event 06: messages = "select * from outbox"

event 07: => messages are now [{msg1, msg2}]

event 08: RabbitMQ.publish(msg1) <--- publishing the second time

event 09: # message persisted to rabbitmq

event 10: Outbox.delete(msg1)

...

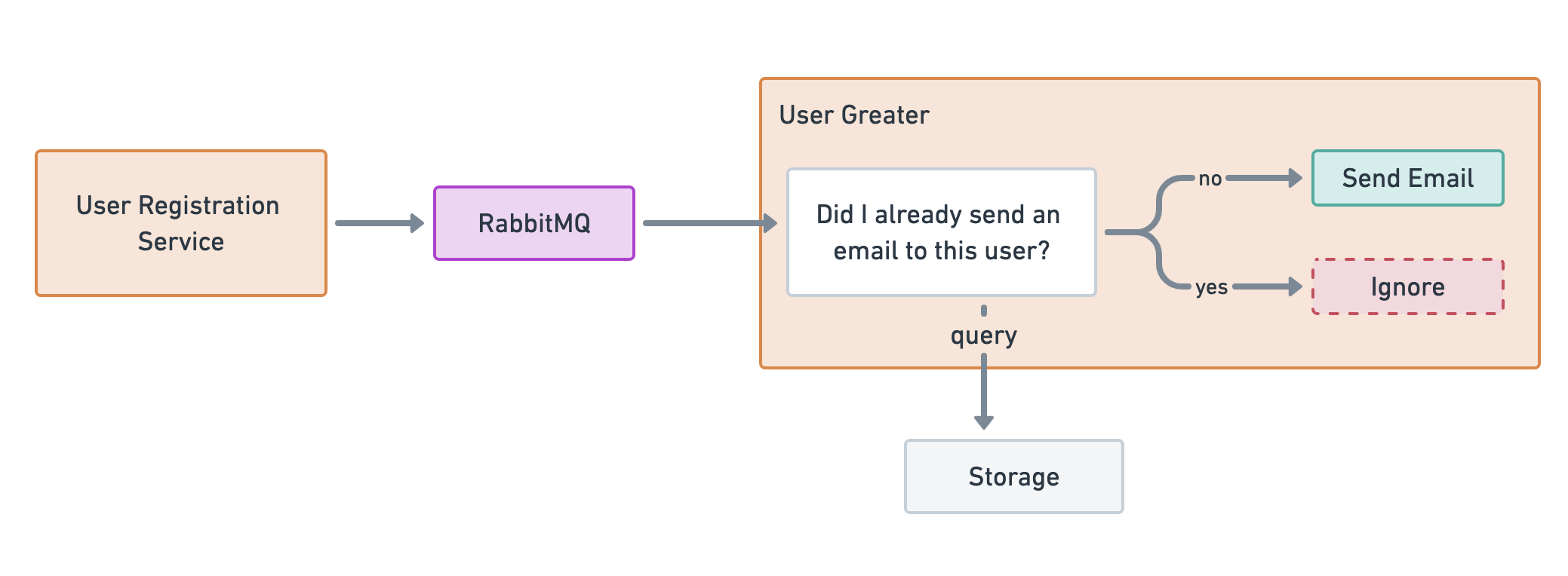

How can clients protect themselves from repeated messages?

Repeated messages can be a real headache. The User Greeter service from our original example will send out to emails. Yikes!

One way to resolve this problem is to make the message receiving endpoint

idempotent. This means if the server receives two messages in, for example

({user_id: 1}, {user_id: 32}, {user_id: 1}), it will disregard the second

occurrence of the user_id: 1 message.

In this case, you will notice that the receiving service needs a way to store the message that it receives.

Let’s look at the implementation:

RabbitMQ.subscribe("user-signed-up") do |message|

email = Email.new(user_id: message.user_id, content: compose(user_id))

result = email.save!

case result

when :ok

RabbitMQ.ack!

when :user_id_already_exists

RabbitMQ.ack! # idempotent, message was already processed

else

# something unknown happened, we don't know what

# let's put back the message to the queue

RabbitMQ.nack!

end

end

Distributed, multi-database systems are complicated. While working on Semaphore, I’ve encountered this and many other tricky problems. If we were lucky, we caught them in during PR reviews, but I also remember several unlucky examples where these bugs caused more severe problems.

Problems in distributed systems show up many months or even years after you introduced them. Usually, this happens when the system hits a critical number of requests. This feedback loop is slow; we must educate ourselves in advance.

Here are some great resources for further reading: